As Brooklyn residents and architects working primarily in the borough, we’ve observed the results of redevelopment in areas of the city which have recently gone through zoning changes designed to increase the local building stock. Over time, the developmental tension between high maximum floor to area ratios on the one hand, and small lots and preexisting buildings on the other, yields a scenario wherein sites are combined, the buildings which previously occupied them are systematically demolished, new buildings are constructed, and with them a new context emerges. But why is this new context so unpleasant, and how could we ensure better results in the future?

Two examples are illustrative:

The stretch of Myrtle Avenue between Washington Park and Bedford Avenue, primarily in the Clinton Hill neighborhood of Brooklyn, was rezoned from R6 to an R7A district in 2007, increasing the residential F.A.R. from 3.0 to 4.0. Prior to rezoning, this stretch of Myrtle Avenue was lined predominantly by three story mixed-use buildings, with a commercial base and residential units on top. It should be noted that this building stock as it stood was already under-built per its previous R6 designation, however the remaining available floor area was not sufficiently large to justify expanding these buildings before the rezoning.

After Myrtle Avenue was rezoned, adjacent lots were aggregated and developed over time to the maximize allowable floor area- and a very different type of building stock emerged. The scale, rhythm and texture – along with the intangible character of the neighborhood – have largely disappeared, rendering the distinction between incremental development and tabula rasa redevelopment ambiguous in this context.

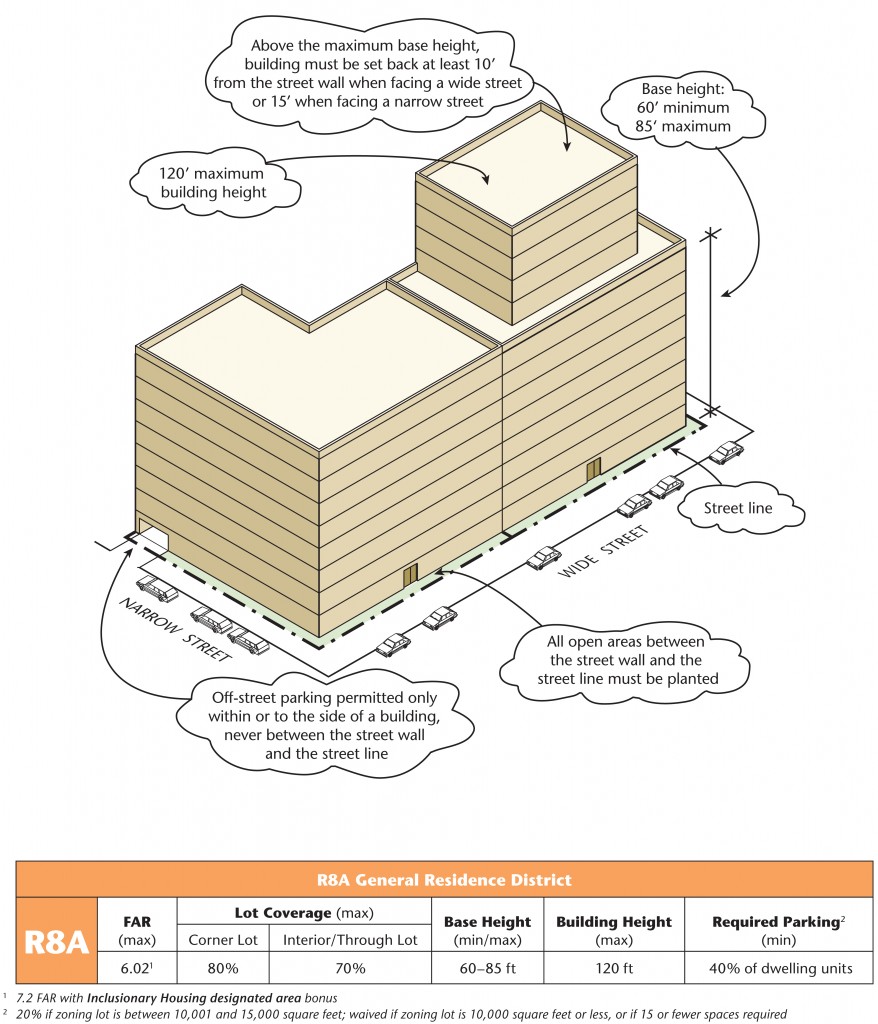

Similarly, 4th Avenue between Atlantic Avenue and 15th Street, which demarcates the border between the Park Slope and Gowanus neighborhoods of Brooklyn, was rezoned from a predominantly R6 district to an R8A district in 2003. In 2006, the R8A district was expanded further south to 24th Street. Similarly as Myrtle Avenue in Clinton Hill, 4th Avenue was defined by four story mixed use buildings with commercial ground floors and apartments above. With the R8A district rezoning, the F.A.R. was increased to 6.02 and a maximum height of 120 feet. This resulted again in the aggregation of sites and the creation of large apartment blocks bearing no resemblance to the pre-existing context.

4th avenue intentionally became the site of large new developments. Part of the impetus for rezoning 4th Avenue was to shift development away from Park Slope, in order to preserve the character of one neighborhood at the expense of another. Formerly known as the Grand Parkway, 4th Avenue in Brooklyn has come to be known as the “Canyon of Mediocrity.” How did this happen?

Both Myrtle Avenue and Atlantic Avenue, after rezoning, became subject to the provisions of the Quality Housing Program. Note the letter suffixes of their district designations: Residence districts with a letter suffix – A, B, D or X – are known within the New York City Zoning Resolution as “Contextual Districts.” In 1987, as a response to public backlash against the modernist tower-in-the-park developments of the 1960’s, the Quality Housing Program was established. It mandated maximum distance between street wall and sidewalk, minimum and maximum street wall heights, and minimum and maximum building heights. Through these mechanisms, contextual districts were intended to maintain and restore the urban fabric of the city. However, beyond an antiseptic prescription of built form, we remain unsure of what “contextual” is actually supposed to mean. Tye term is not clearly defined in the text of the NYC Zoning Resolution. We take it to mean that buildings are supposed to “fit in” – among each other or within existing context. While the zoning diagram itself allows for some degree of flexibility, the housing developments that it has generated fit into a rather narrow array of possible outcomes.

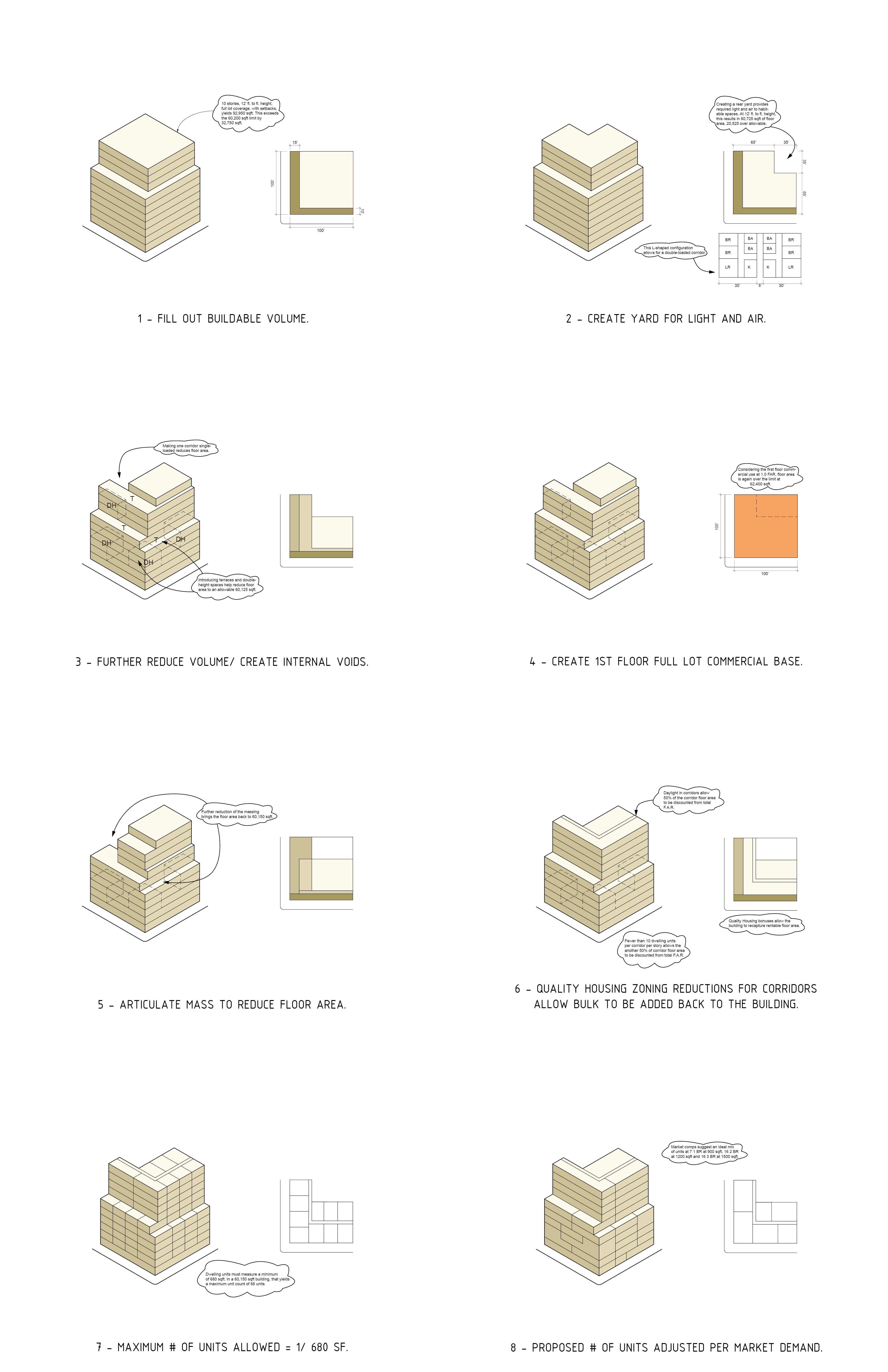

Indeed, the narrow array of possible outcomes is due to the unfortunate process by which these buildings are laid out. Floor area is increased as a building is planned by maximizing lot coverage, increasing floor count, increasing building height, increasing base height and minimizing setbacks. Floor area is decreased by introducing courtyards, lowering base height, increasing setbacks, or introducing double height spaces. All of these mechanisms are negotiated around a maximum allowable F.A.R. for any given district, to produce a non-specific volume which is then subdivided into a mix of apartment sizes appropriate for market conditions. This configuration may even change after construction begins and newer market information becomes available over the course of the building’s development. The zoning diagram becomes, in effect, an empty vessel that allows for a limited variety of formal outcomes, which functions as a delivery method for commodified real estate. The outcomes tend to be surprisingly retrograde. They produce urban environments which are every bit as stultifying – albeit in a different way – as the housing projects of the postwar period.

How To Develop an R8 Building in 8 Simple Steps:

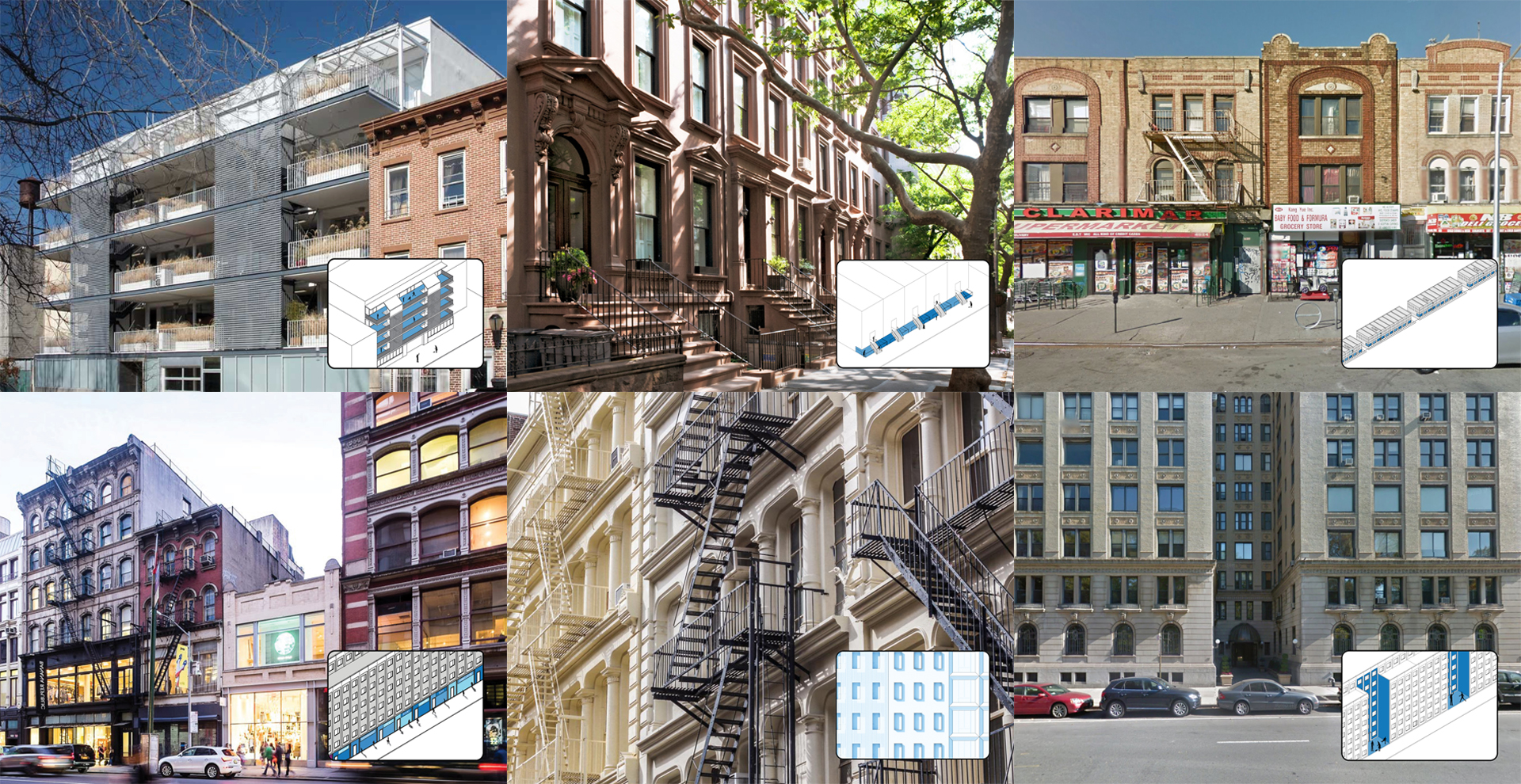

The urban environments resulting from this approach to housing development are objectively lacking many of the characteristics that work together to create the urban environments we cherish. While it is tempting to default to familiar historical styles in an attempt to revive what has been lost in contemporary development, it is imperative that we identify the formal and spatial devices which operate independently of aesthetics, so that we are equipped to design delightful urban conditions, whether futuristic or historical in their appeal. Some of these devices are porosity, scale, texture, rhythm and identity.

Multiple versus single entry points, stoops and front gardens versus flat street walls, balconies and entry courts: all are devices which conspire to dissolve the barrier of the building envelope into an occupiable border between the privacy of the interior and the public openness of the street. This really matters in a city as dense as New York, because it modulates the relationship of a resident to thier neighbors – it allows strangers a glimpse just beneath the surface of our private lives and affords the passerby some reassurance of the watchful eye of his neighbors. Jane Jacobs discussed this phenomenon at length in her analysis of American cities in the 1960’s.

To be sure, contemporary building practices are partially responsible for the absence of these articulate conditions in the examples of Myrtle and 4th Avenues. Curtain walls, and more commonly among residential developments- rainscreen systems, are thin assemblies which are hung from a building’s frame. Rainscreens utilize a thin cladding material with an airspace in front of a primary waterproofing membrane. This method of assembly tends towards a a least common denominator of “wallpaper architecture,” where the building’s facade presents a flat, graphic image without any true three-dimensional tectonic quality. This contrasts with the architecture of beloved old neighborhoods which, thanks to the building practices at the time, naturally acquired facade depth and articulation, cast shadow and shape space.

Old building practices, in addition to prompting volumetric articulation of facades, also lent consistent material palettes to the neighborhoods where they were deployed. There is a certain serenity to a scene of material uniformity, especially when juxtaposed with the garish cacophony characteristic of new developments. However, this material consistency itself fades from attention, allowing the spatial and formal qualities of a building to stand out. The qualities and materials emphasized by old building practices are therefore mutually beneficial and self-reinforcing – the limits of masonry construction prompts a fine-grained three-dimensionality, while the uniform materiality of masonry construction throws that three dimensionality into yet sharper relief.

How can we negotiate these two realities – the flatness of contemporary construction methods and the obsolescence of provisions governing bulk within Contextual Zoning Districts?

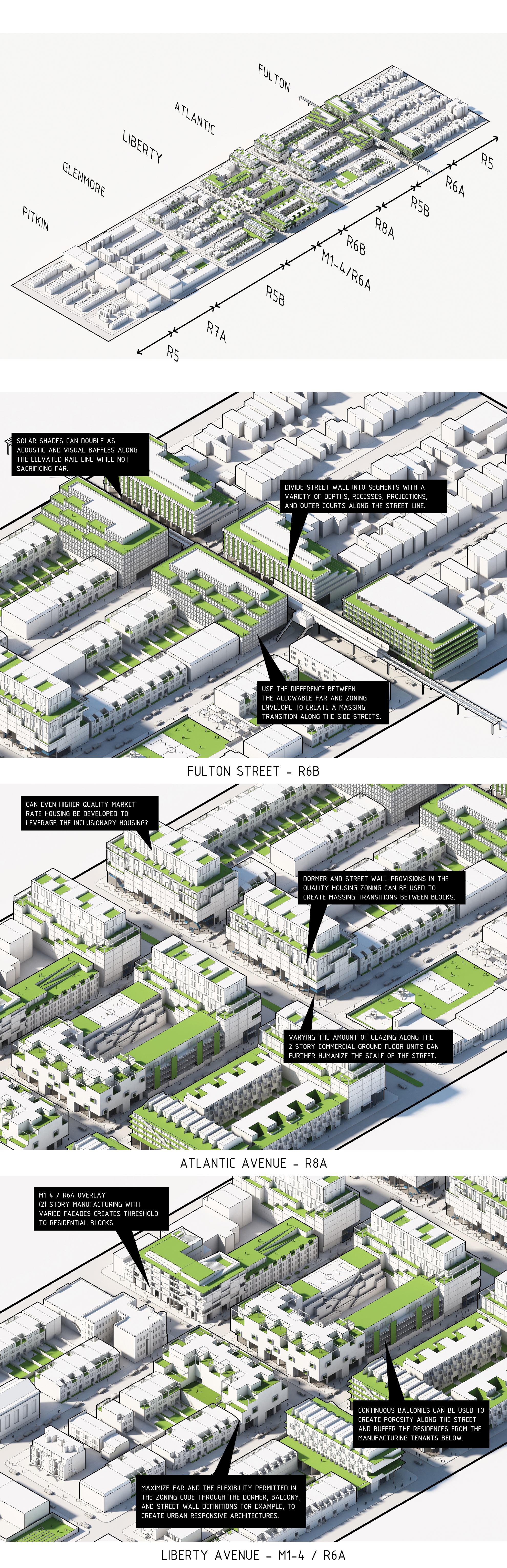

Given a reasonable understanding of the zoning code, market forces, a neighborhood’s needs, and of the building characteristics mentioned above, it is no doubt possible to design inspiring urban environments in the present day. City Planning has worked very carefully with the local community in Brooklyn and their district councilman, Rafael Espinal, to create a plan that is both a development opportunity and which thoughtfully engages the existing community’s needs. While this plan includes a tactical overview of projected development sites, we are interested in testing the limits of the zoning diagrams in the context of what an extensive build-out over the coming decades might look like. What we are seeing now on 4th Avenue has been a decade in the making. For this experiment, we have examined the area of East New York between Hendrix Street to the east and Bradford Street to the west, and modeled the potential as-of-right development with the goal of testing the limits of the current zoning diagrams. What kind of architectures and neighborhoods might arise in response to the existing and the future contexts of this district? The neighborhood includes existing assets such as Glenmore community gardens, several local churches, schools, daycares, a fire department, and J/Z/A and C train subway stations. While existing East NY may appear under-developed compared to the potential up-zoning, every block of the district has a rich community fabric. How can we image building out the as-of-right FAR and zoning in this diverse district while maintaining architectural and urban relationships to the existing forms and at the same time anticipating the extent of developments that will take place over the next decade? We modeled the maximum density for each street and then zoomed in to articulate the results. Within the mandates of the Quality Housing Program, the difference between the maximum envelope and the maximum floor area allow us to terrace certain building masses as the different districts converge between main avenues and side streets. Further facade articulations are utilized to create exterior courts, more human-scaled building massing and highly porous facades.

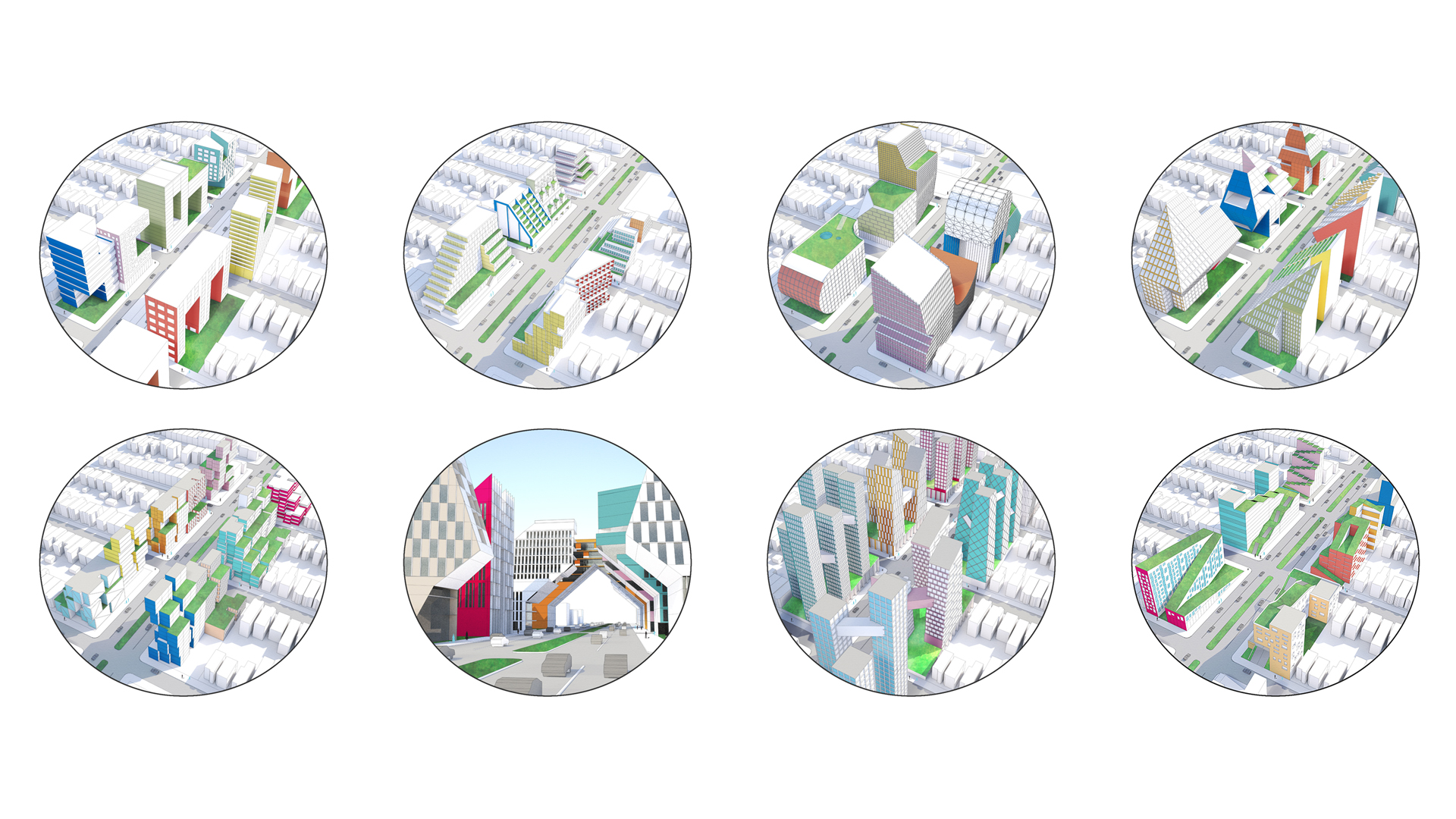

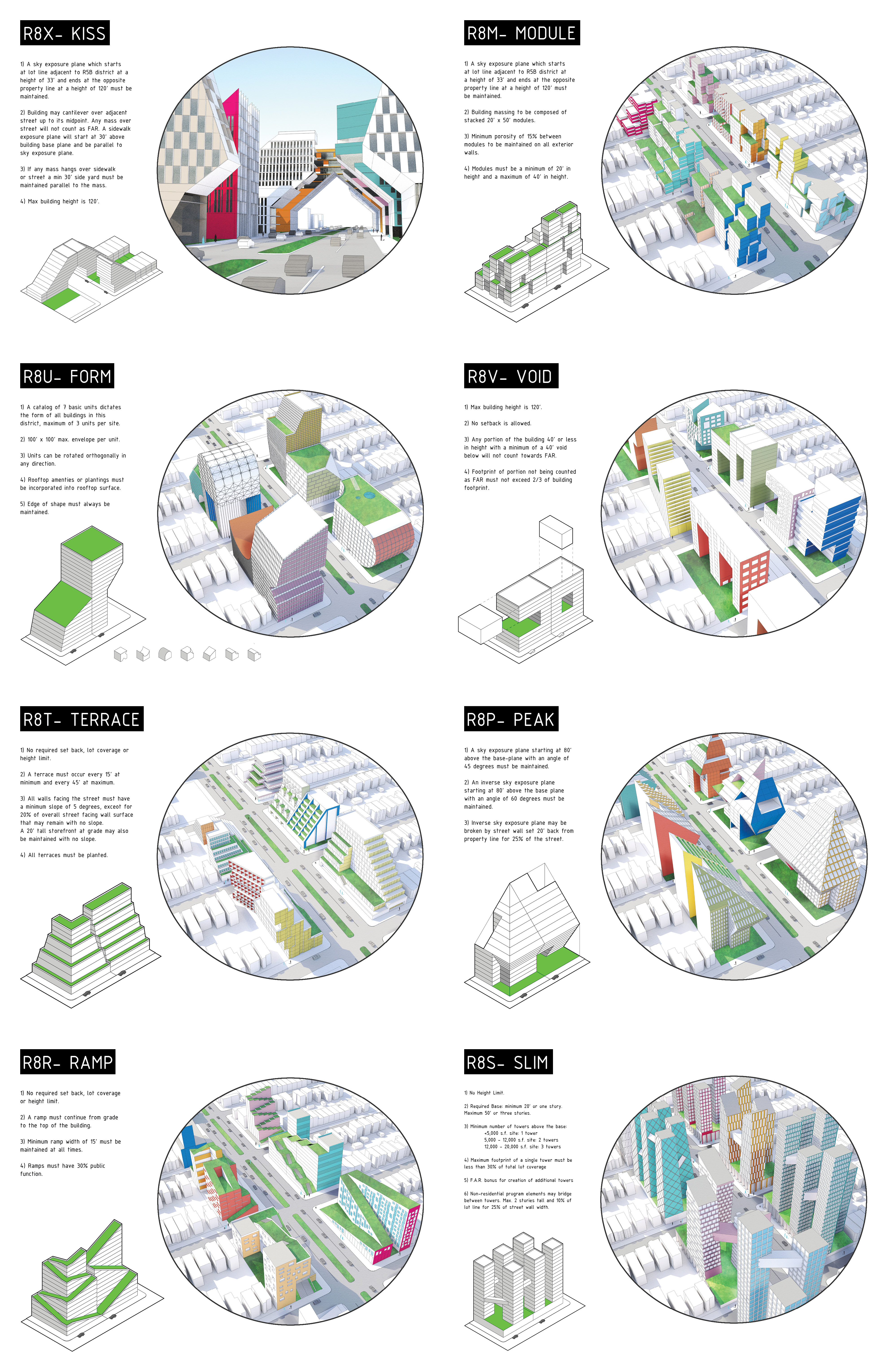

Of course, we could also speculate what’s possible if we change the rules of the game. The gravity of the lowest common denominator cannot simply be ignored when market forces are harnessed as the driver of development. The parameters of the diagram produced by the Quality Housing Program require a formal consistency among all contributors, and therefore they tend to create context through their similarity and repetition. These regulations fall short, however, of creating the possibility for a real urban re-design. OPerA Studio and OPA have taken on the project of expanding the rules or creating altogether alternative series of rule sets that would create radically different contextual districts, using East New York as a testing ground. The eight diagrams below illustrate these speculative, imagined rule sets for zoning regulations and the resulting new spatial experiences. For instance, what would happen to the streetscape if buildings featured large, mandated voids to let through more light? What if the roofs of buildings were required to continuously ramp from street level to the highest point of the building- how might street life “climb” up this alternative landscape? What potential does an avenue of slim, clustered and interconnected towers have to surprise and delight? We have explored how incentives for developers like increased F.A.R. and height limits – the same found in Quality Housing Districts – can be paired with parameters that create inspiring urban conditions.

East New York was recently rezoned, most prominently along Atlantic Avenue from C8-2 and M1-1 commercial and manufacturing districts of 1.0 – 2.0 F.A.R. to an R8A district of 6.02 F.A.R. As part of a continuing topic of research, OPerA Studio and OPA have presented alternative zoning diagrams at the New York Build 2017 Expo on March 17th, and will present further findings in the future. The changes in zoning which provide the backdrop for this research and exploration create the potential for extreme change. In the near future, East New York will not look as it does today. The only question is, can we prevent it from becoming another canyon of mediocrity?